The text below is a recap from Rinke Hendriksen’s EthCC [4] talk “Hello World, Swarm” from July 2021. In it, he gives a concise but complete introduction to the inner workings of the Bee nodes that make up the Swarm network.

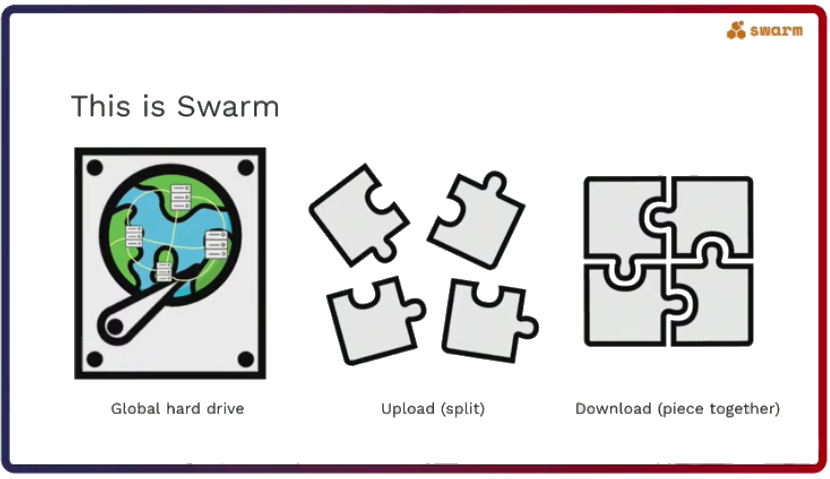

Swarm, a global hard drive

Rinke sees Swarm as a global hard drive hosted by computers across the globe, which collaborate because they are incentivised to do so. Just like a normal computer, files and websites can be uploaded and downloaded to and from Swarm.

The difference is that uploaded files are split into smaller pieces of data called chunks and distributed to nodes all over the world. Downloading in this context is essentially requesting these pieces and puzzling them back together, Rinke explained. It is only for the person who requests specific content that these chunks make sense.

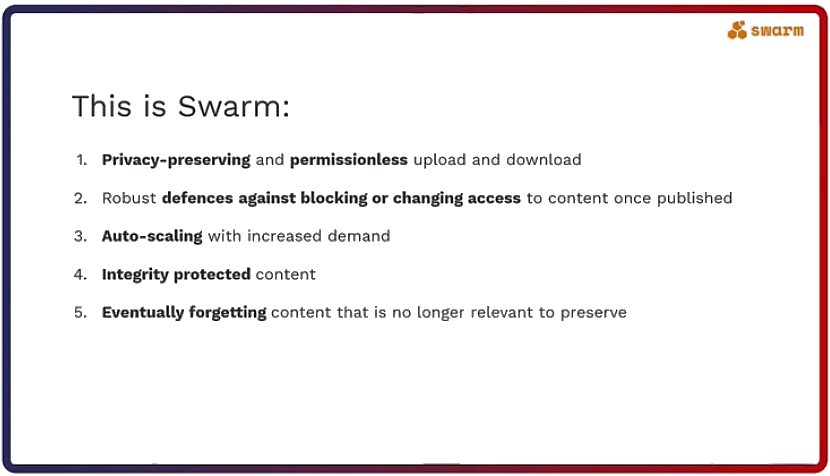

Being this global hard drive gives Swarm some unique properties listed in the figure below.

How Swarm works

The first thing to keep in mind, Rinke began the next section, is that Swarm is not a regular piece of software. It doesn’t just run on one computer but it is a collaboration of nodes who “talk” the same protocols and run the same software, called Bee.

He continued by listing the benefits of becoming a Swarm node operator: “There are two reasons why a person would run their own node. The first is that they get access to the Swarm network, so they can upload and download files. And if you have an old computer lying around you can actually earn some money from your spare bandwidth and hard drive capacity”.

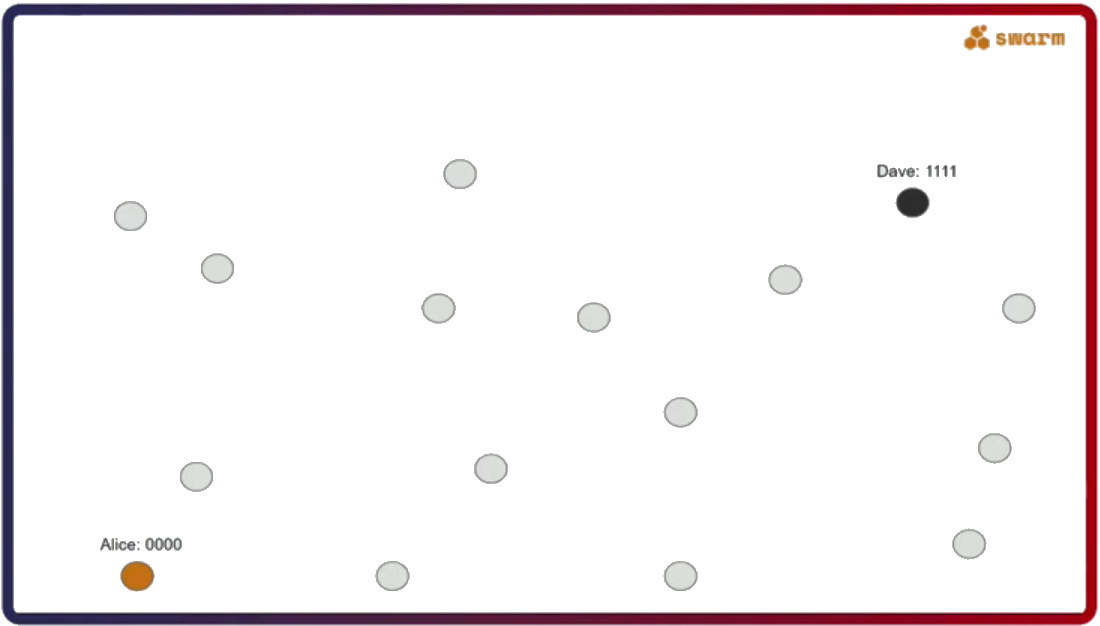

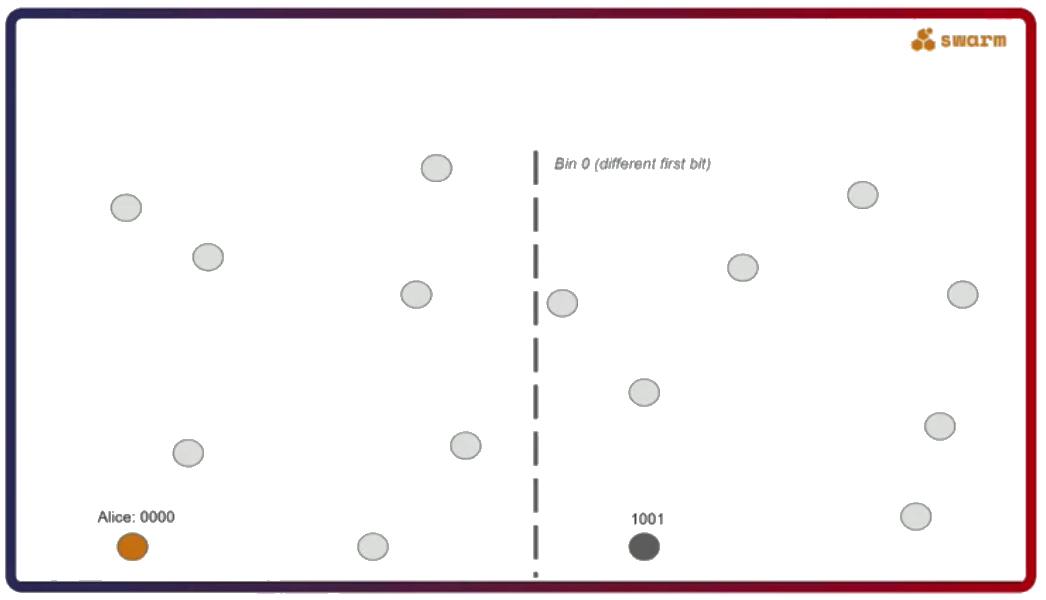

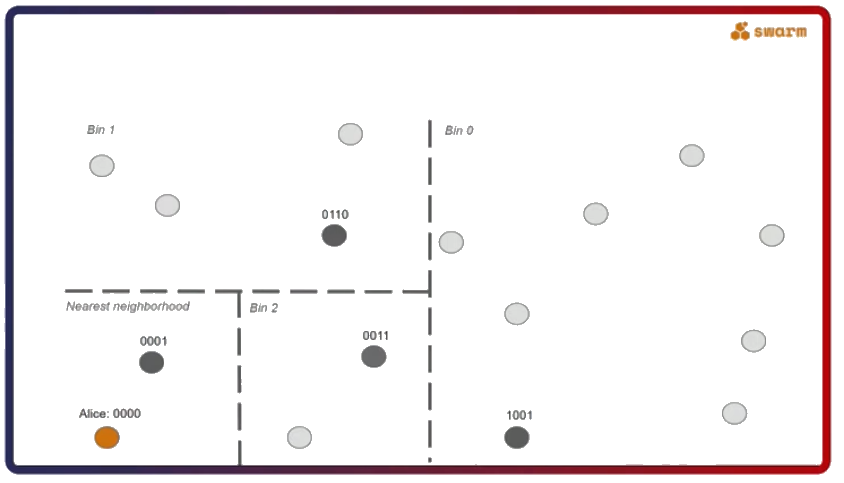

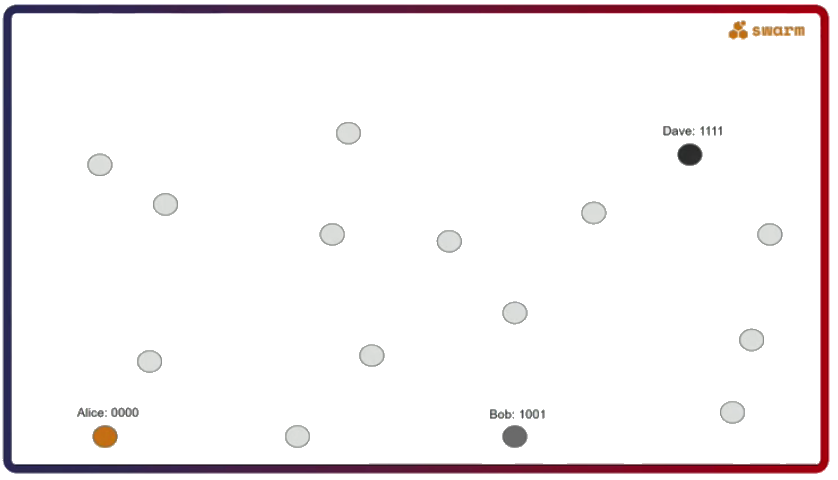

The second important thing about Swarm is that its network uses a specific type of a distributed hash table called Forwarding Kademlia. Let’s say Alice (address 0000) wants to send a message to Dave (address 1111). The question here is, what kind of a connectivity pattern does Alice have to follow to always be able to send a message to Dave?

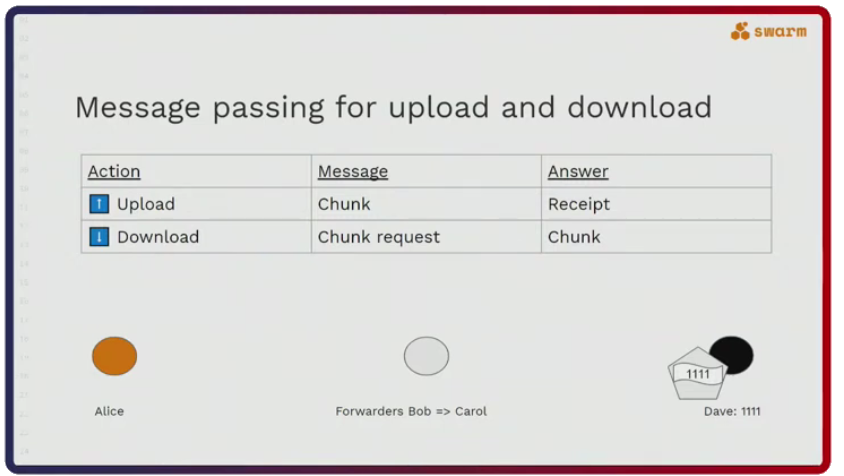

What happens is explained in the figure below. Alice sends a message for Dave to Bob. Bob still doesn’t know who Dave is but he does know Carol, who is more likely to know Dave. He forwards her the message and since Carol actually knows Dave she sends the message to him. The exact opposite route happens when Dave sends a message back to Alice.

Chunks are the key

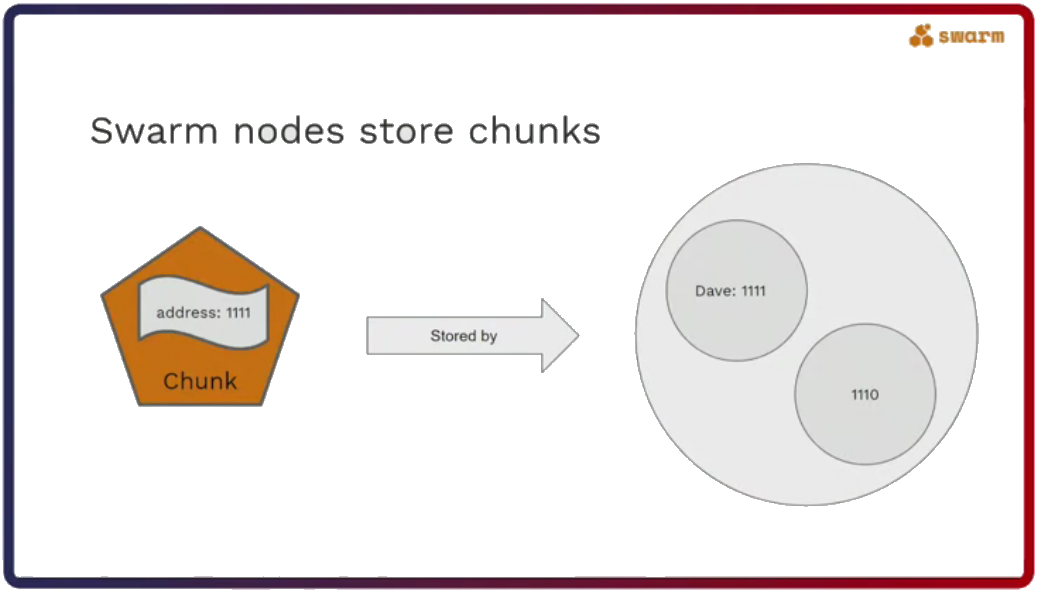

But Swarm nodes don’t just forward messages. This is reserved for uploading and downloading data. They also store chunks, which contain data and have an address. As Rinke pointed out in his talk, chunk addresses are very important because they determine which nodes will store them. Nodes will store chunks with similar addresses. Also, the same chunk will be stored by multiple nodes to provide redundancy in case nodes come and go from the network.

The chunk address is provided by the hash of the data or is attested to by a digital signature of the uploader to provide the integrity of the data.

This design has an important consequence. Nobody in the forwarding chain knows who the originator of the request is. The forwarder only knows that the request is coming from the currently requesting node. “This facilitates the privacy of whoever is downloading via Swarm,” Rinke says.

Why do nodes help each other?

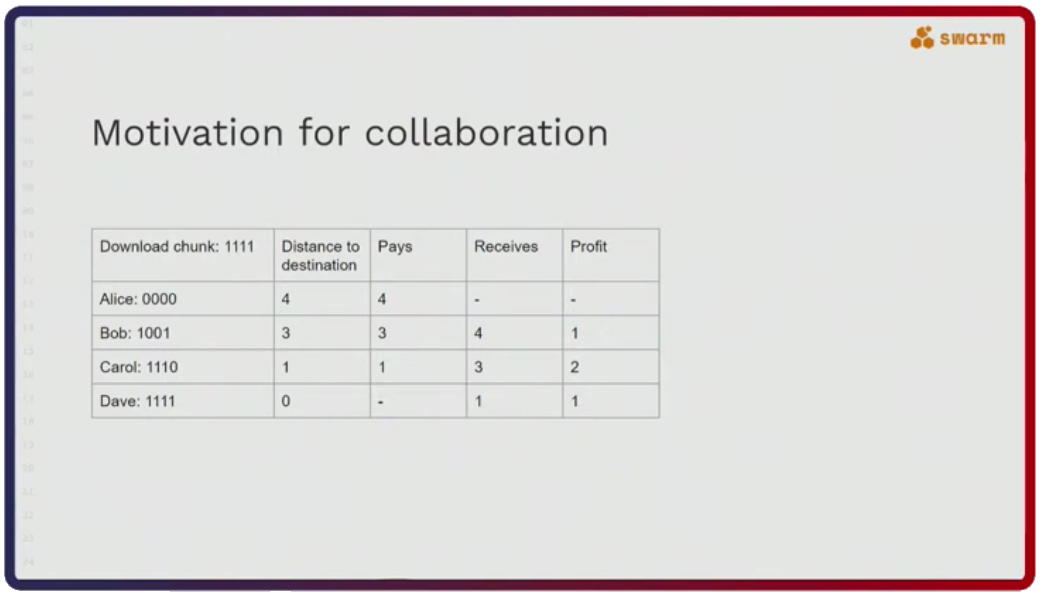

The reason nodes act in this collaborative way is because they are financially motivated to do so. Alice has to pay to receive the desired chunk and the payment amount corresponds to the distance the chunk has to travel. The payment is also dispersed along the forwarding chain so that each node pockets some profit (see figure below). The profit is paid out either in Swarm’s native token, BZZ, or in reciprocal services.

What if Swarm runs out of space?

Just like any other hard drive, Swarm has a finite storage capacity. Unlike a regular hard drive, once the content is published it cannot be changed and nobody can revoke access from anybody. Meaning, as Rinke put it, it does not have a deletion operation.

“Basically, how we do this is that every chunk has a payment reference, which signals the value of that particular chunk. These on-chain payments together with some expected profit measure allows the nodes to order the chunks based on their value. That’s how only the most relevant chunks are preserved in Swarm. And those chunks that are not requested that much eventually get replaced,” Rinke laid out Swarm’s “garbage collection” framework. Swarm, therefore, always preserves the content that is the most relevant to preserve at a given moment.

Swarm and Web3

Although the greater part of the talk revolved around Swarm’s DISC (Distributed Storage of Chunks), the final part of the talk focused on how Swarm actually fits into the Web3 narrative.

“Just as the hard drive on its own doesn’t really give meaning to the data, the DISC doesn’t give meaning to the chunks. It’s the data structures and how we interpret those chunks that gives meaning to them,” Rinke added.

With the Bee node you can request files, directories, and dynamic content and send messages in a permissionless and private manner. These capabilities together form the puzzle pieces that enable decentralised applications on top of Swarm.

And these applications can be whatever developers choose to build. The sky’s the limit!

Discussions about Swarm can be found on Reddit.

All tech support and other channels have moved to Discord!

Please feel free to reach out via info@ethswarm.org

Join the newsletter! .